Meanwhile, thanks to our friends over at The Big Smoke, we have permission to reprint this terrific article by John Bell: artistic director of Bell Shakespeare and passionate advocate of new work.

DISRESPECT

WRITERS AT YOUR PERIL

John Bell

Many years

ago I was in a commercial production of a new play and some of the actors were

being pretty free-and-easy with the text – throwing in gags, ad-libbing and

paraphrasing.

The director

gave them a roasting.

“Stop mucking

about with the script – it’s illegal and it’s immoral!”

That gave

everyone pause for thought.

Sure, we

understood there was a contractual obligation to get the author’s words right –

but immoral?

The more I

thought about it, the more sense it made. Having worked with so many

playwrights over thirty years, and now having one for a daughter, I have come

to appreciate how much agonising goes into constructing every piece of

dialogue: the re-writes; the scratching-out and starting again; polishing draft

after draft in workshop after workshop.

When the

thing is finally on paper it bears the author’s name and he/she will be judged

on what is uttered on the stage. Some playwrights, especially of the Y

generation, are happy to collaborate and involve the actors in the creation of

dialogue. Some rely heavily on a “verbatim” theatre technique, adapting and

reshaping words overheard in the street or recorded in interviews.

But to

playwrights of a generation or two ago that would be anathema. The play was

conceived and composed in an ivory tower and handed over to a theatre company

with the threat of legal action if a word or comma was changed without

permission.

I guess a

playwright is free to choose by which route a text is finally achieved, but I

sympathise with writers who demand that the script, once agreed upon, should be

stuck to.

A recent case

in Western Australia highlights the situation.

A fierce

split occurred between the Perth Theatre Company and the author of a play it

had commissioned. Ironically, the play was titled Alienation. The

author, Lachlan Philpott, claimed that thirty percent of his text

had been cut without consultation, stating that the script had “been very

significantly altered to the extent that it does not represent the script of

which he is the author”. He went on to state that this was “a sad indication of

the way that playwrights are viewed in some parts of the theatre sector”.

He was

supported in this by the Australian Writers’ Guild (AWG) Playwriting Committee,

which issued press

releases calling

for “respect for writers and new Australian work”.

The Q

Theatre, Penrith, co-producers of “Alienation”, cancelled their season in

support of Philpott.

A number of

playwrights have expressed concern about a conspiracy against playwrights, and

Rosemary Neil, writing in The Australian accused

a particular theatre company of a “deep-dyed ideological bias against

text-based plays”.

Supremacy in

the theatrical hierarchy is constantly shifting, and in my time I have lived

through eras variously dubbed “Writers’ Theatre”, “Directors’ Theatre” and

“Designers’ Theatre”. At times, the actors have revolted and established

Actors’ Companies where directors and designers were generally dispensed with,

and the spotlight focussed on the performers – two planks and a passion.

Despite the

domination of any one faction, theatre has always tolerated alternative forms

running alongside the mainstream; a lot of popular theatre has never been

text-based. We have virtually no textual records from nearly 400 years of

commedia dell’arte. Circus, vaudeville, music-hall and (needless-to-say) mime

have left us a few photographs, stage directions and snatches of song, and the

few scripts that remain are lifeless without the comedians who created them.

Right now we

are seeing a lot of theatre that is verbatim, or physical or musical, created

by teams of “theatre workers” or “theatre makers”. The old denominations of

director, writer, designer, performer have been blurred or dispensed with. This

is all fine and dandy, and can happily co-exist with “writers’” or “text-based”

theatre, as it has done in the past.

There is room

for all.

But to add

fuel to the fire, we have the controversy about re-writing the classics, a

phenomenon that has managed to get up the noses of disparate groups. The

academically inclined protest that it is an insult to the likes of Chekov and

Strindberg to rewrite their plays, but retain their titles. Not only are Chekov

and Strindberg quite good enough as they are, goes the argument, but it is

seriously misleading to sell tickets to a classic you are not going to see.

Quite a few

playwrights feel aggrieved too because, they say, these works are taking the

place of new Australian plays, and, with their generally sizable casts and high

production values, soaking up resources. Most Australian playwrights don’t dare

aspire to a cast of more than four or five if the show is to have any hope of

getting on. Playwright Stephen Sewell has entered the lists, proclaiming that

theatre companies should not pass off adaptations as new Australian works and

condemning those arts bureaucrats who let the companies get away with it.

The word

“immoral” springs to mind again.

Is it fair

trading to sell a new work under the guise of a classic title?

How many

years does it take for the text to become common property to be reworked,

pillaged or hacked about at will?

This goes

beyond the mere issue of copyright to the deeper issue of respect for a

writer’s work and reputation.

For the sake

of our own cultural tradition, should we be obliged to respect the integrity of

classic texts, or are they to be regarded as just so much raw material for

“theatre workers” to play with?

If so, the

gulf between theatre practice, and academic research and commentary can only

become wider.

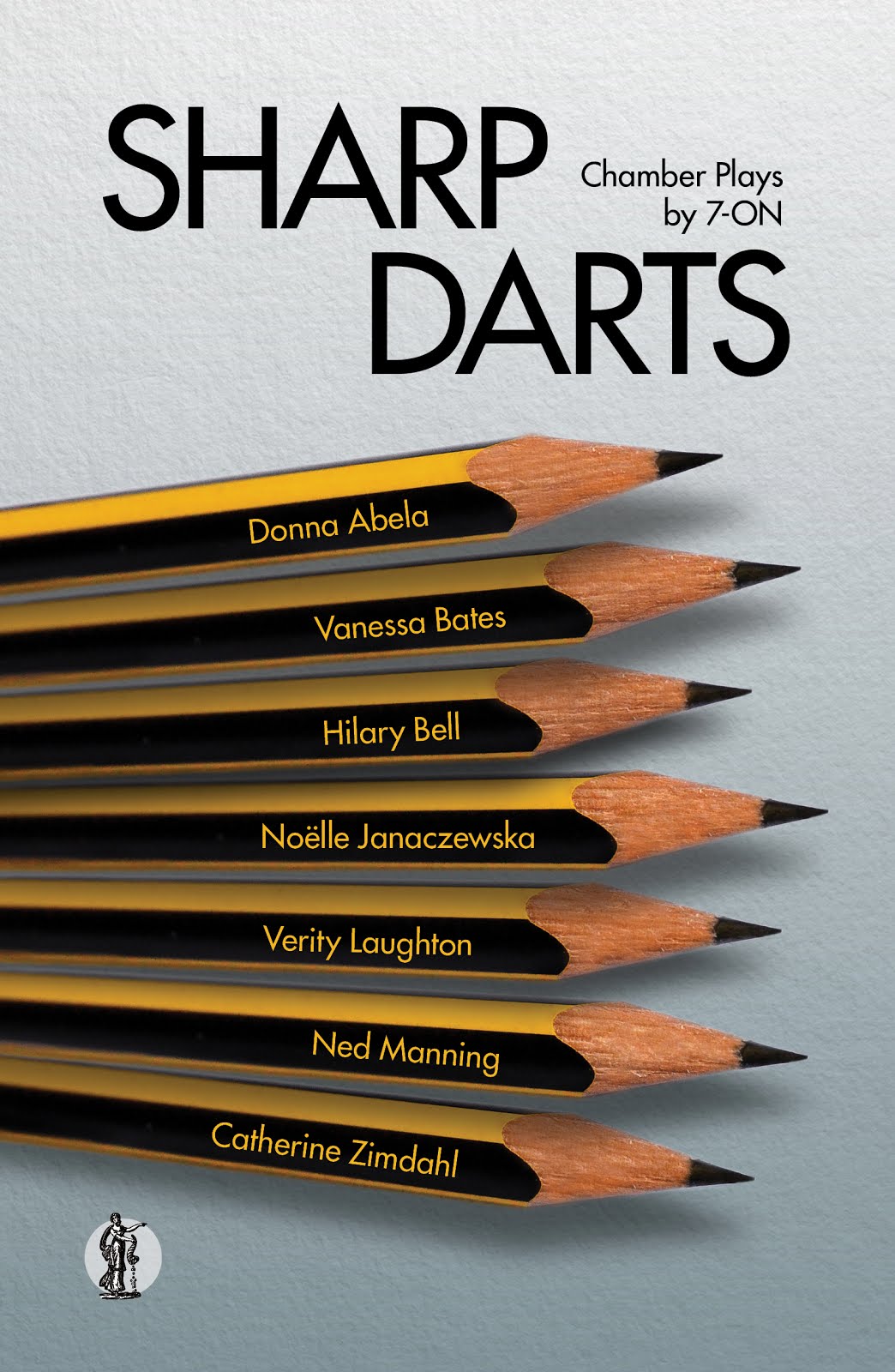

The

Playwrights’ Group called 7-ON say they have no problem with classic

adaptations as long as they don’t replace new work. They also point out that

“adapting” a classic is a lot easier than creating a play from scratch and,

moreover, “No new plays – no new classics”.

It is

undeniable that text-based theatre is one of the cornerstones of Western civilisation,

from the Greeks through to the Elizabethans, to Wilde and Chekov to Miller,

Beckett and Brecht. For many of us, the greatest experiences in the theatre

have been when a great text is brought to life by a team of director, designer

and actors, everyone collaborating to serve the whole rather than any one part.

If theatre in

Australia is going to flourish we have no option other than to treat

playwrights not just with respect, but with enthusiasm and encouragement.

Theatre

companies must nurture writers by granting them internships, opportunities to

live within a theatre community and feel themselves to be a part of a creative

process. If writers are employed as dramaturgs for a period of time they can

make valuable contributions to the work in hand, as well as have the chance to

develop their own craft in a stimulating, inclusive environment.

Although a

“classical” company, Bell Shakespeare employs dramaturgs and commissions new

work through its development wing, ‘Mind’s Eye’, where five writers are

currently working on commission. The Sydney Theatre Company hosts the Patrick

White Fellowship, and both Griffin and La Boite offer writers year-long

residencies.

A lot more

needs to be done and many more opportunities created to give new work an

airing.

Every

theatrical generation is defined and assessed by the body of work it leaves

behind – and that means texts.

The rest is ephemera.

Remember: If

there are no new plays, there will be no future classics.

January 31, 2014

Originally published on The Big Smoke [http://thebigsmoke.com.au/2014/01/31/disrespect-writers-artistic-peril/]